Breaking Down the Buzzword: Storytelling

“Your campaign should tell a story.”

If you work at a marketing firm or had a marketing firm pitch you, you’ve probably heard this phrase before.

This is bad advice. It’s fundamentally incorrect. And it’s attitudes like this one that are responsible for bad pitches, activations, and campaigns.

The problem with this advice is that it assumes that you’re only telling a story when you intend to. The thing to remember is not that your activation should tell a story but that it does tell a story. In fact, everything you do from pitch to sizzle tells a story. Everything you ever do that’s seen by another person — from the way we ride the subway to the way we socialize at parties — tells a story.

What makes marketing firms so powerful — and particularly experiential marketing firms — is that they are intentional about what stories they tell and how they tell them.

How Stories Work

It’s tricky stuff trying to define the word “Story.” There is an entire field of study dedicated to this issue (narratology) and there are as many opinions on the matter as there are books discussing it. But utilizing storytelling in a marketing campaign doesn’t require that we develop a strong stance on whether Mark Twain’s definition is better than Wikipedia’s. It merely requires that we understand how stories work and why they’re useful to us.

When it comes to the question of how stories work, Narratologists still have lots to say, but opinions are not quite as varied (or abstract) on this point. Aristotle’s Poetics, Freytag’s pyramid, and Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey cycle are some of the best-known articulations of story mechanics. And while each illuminates and elaborates upon different aspects of storytelling, they all agree on the fundamentals of how stories work. It doesn’t matter much which of their philosophies we use to explore the role of storytelling in marketing.

So we won’t use any of them.

Instead, we’ll use Dan Harmon’s.

If you know of Dan Harmon, you probably know him as the comedy television showrunner who brought the world Community and Rick and Morty. Harmon’s philosophy of storytelling (which is really just Joseph Campbell sans Carl Jung) — has become fairly popular since superfans of Community first noticed strange circular diagrams popping up in the background of the show.

In response to fan curiosity, Harmon published his delightfully-simple approach to diagramming story. It’s a circular philosophy, but not in the bad way. And it’s been making the rounds for years.

The blog series is worth a read, but for the short-on-time, here’s the reductive gist:

A story introduces us to a character who wants something. The character enters a new situation, adapts to it, gets the thing they wanted, and discovers that the thing comes at a cost. Then the character returns to their regular lives having learned something. (This last step is best epitomized by the fable’s moral-of-the-story.)

Or to put it even more simply: characters enter into new situations and return changed.

Harmon is careful to clarify that all stories work this way — that even student filmmakers who try to break these principles of storytelling will inevitable fail. Film a plastic bag floating around an alley and viewers will impose a cyclical narrative on that video. (See Ricky Fitts’s home video and Katy Perry’s interpretation of it.)

The value of understanding how stories work isn’t that it makes storytelling possible; it’s that it makes good storytelling possible.

Storytelling in Marketing

We said that in stories, characters enter into new situations and return changed. In marketing, the character is the consumer. The new situation is their interaction with the brand or product. The return comes when they’ve finished the interaction and return to their routine. The change speaks to their opinion of the brand/product post-interaction. In experiential marketing, the change may also refer to a change in the person — their day, their relationships — they may have learned something new, had a bonding experience with a loved one, etc.

As we’ve said, any activation is going to tell a story with this structure. But marketing firms that are intentional about their storytelling have two advantages.

First, intentional storytellers are able to make the activations more memorable and clarify their messages for consumers. They do this by calling more attention to each of the story beats and to the story arc as a whole.

Take, for instance, experiential marketers who sell soda. Most give their attention to sampling: they want consumers to try the drink and discover that it tastes good. That’s a story, sure, it’s just not a very good one.

When we were asked to help sell Mountain Dew, we got intentional about our storytelling. We took the “enter into a new situation” beat very seriously. You could even say we did some world-building.

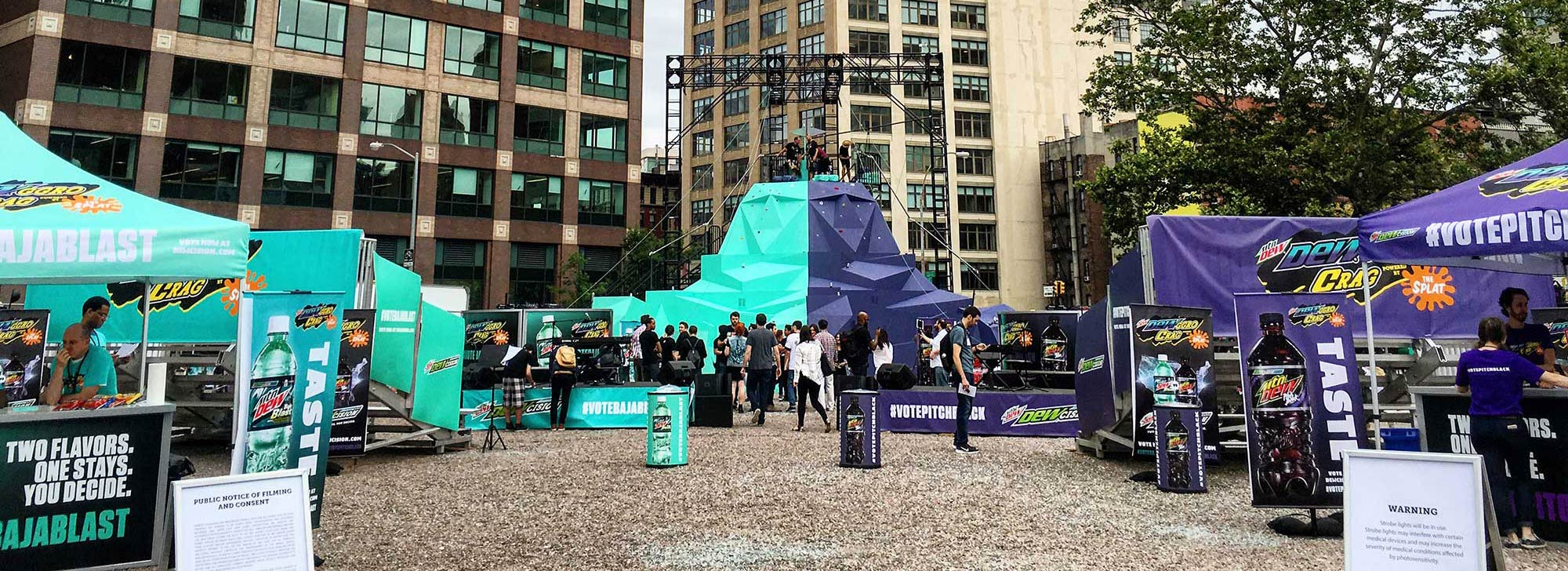

Of course we offered tastings, but we also built a mountain in the middle of New York City (we called it “The DEWggro Crag,” in partnership with Nickelodeon) and challenged consumers to race to the top. We featured battling musicians and competitions of all sorts. What we offered wasn’t just a sampling story; it was an adventure story. And the moral of the story wasn’t just that Mountain Dew tastes good. We also conveyed that it’s the drink of fun, competitive thrills.

The second value of considering story when you market a product is that it helps you keep your eye on the prize: a positive, memorable consumer interaction.

Particularly in traditional advertising, marketers have a tendency to prioritize exposition: they want to tell consumers what a product does and how it will make their life better. In contemporary advertising, this messaging is usually couched in fictional storytelling. (Dad buys a new cereal that makes the dog wear sunglasses and skateboard; the attractive coworker becomes interested when the balding employee switches deodorants.) The Superbowl and various ad awards celebrate these stories.

But what traditional advertisers almost always forget is that the content of the ad isn’t the whole story. It’s more like the story-in-the-story. The larger story is the one about the consumer’s experience — the marketing event itself. Watching the ad. And for many consumers this is a negative experience: it’s the story of how an ad hijacked their viewing or listening experience to sell them something.

Traditional advertisers usually aren’t sensitive to this. Nor are they sensitive to problems inherent in over-saturation: the more consumers are forced to experience the same ad, the more hostile they become toward the ad and the brand itself.

This is the sort of dangerous thinking we mentioned at the beginning of this article: traditional advertising usually assumes it’s only telling a story when it wants to — when the ad begins. This perspective forgets that everything the brand does tells a story. That includes the very act of airing an ad in the middle of a season finale. Or airing the same radio ad over and over while rush hour traffic holds consumers hostage. Here, the presence of an advertisement is telling its own story — one that is often more powerful than the story that the ad intends to tell.

By contrast, as experiential marketers we appreciate the power of the broader story. We know that what matters most is a strong finish: consumers should conclude the brand interaction and return to their routine changed for the better. To that end, we prioritize the consumer’s personal experience. Our priority isn’t to write a funny radio spot; it’s to give consumers positive, memorable interactions with brands and products. Sometimes funny fiction can be a good way to add value to people’s lives, but more often, we find that what matters are the stories of consumers’ rides to work and weekends off — their quality time with the family and hilarious moments with friends.

Which is why we got in this business in the first place. As an experiential marketing firm, we don’t communicate by allegory; in experiential marketing, consumers are the heroes of their own stories.

We put storytelling first, which empowers us to create impressions of the highest quality.